Desperate Doctors

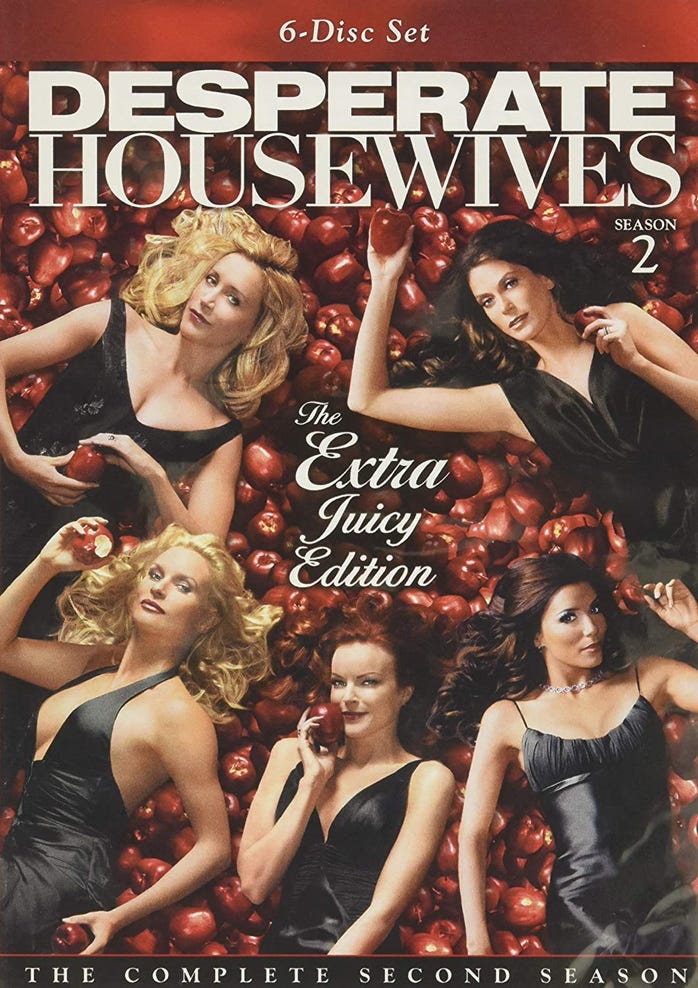

Did you ever watch the TV show Desperate Housewives?

Well . . . this is Desperate Doctors. Doctors used to make a good living. Then came the “team” of Nixon, Erlichman and Edgar Kaiser (of Kaiser Permanente)

The [phony] reason for introducing HMOs into health care was to lower costs. The real reason was to [maximize] corporate profits. This is borne out by an excerpt from the Nixon tapes in a transcript of a 1971 conversation between President Richard Nixon and his aide, John D. Ehrlichman, that ultimately led to the HMO act of 1973.

Nixon: “You know I’m not too keen on any of these damn medical programs.”

Ehrlichman: “Edgar Kaiser is running his Permanente deal for profit—And the reason that he can do it—I had Edgar Kaiser come in—talk to me about this and I went into it in some depth. All the incentives are toward less medical care, because . . . the less care they give [patients] the more money they make.”

Nixon: “Fine.”

Ehrlichman: “. . . and the incentives run the right way . . . ”

Nixon: “Fine.”

From

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2767633

we read

COVID-19’s Crushing Effects on Medical Practices

Some Might Not Survive

By Rita Rubin, MA

JAMA. 2020;324(4):321-323. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.11254

Restaurants and retailers aren’t the only small businesses that have taken a financial hit during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic.

Physicians in small private practices around the country have reported steep declines in revenues, drops so significant that some of them and their supporters have turned to GoFundMe—the platform best-known for helping patients pay their medical bills—to raise funds to help pay their overhead. Telemedicine has helped pick up only a small portion of the slack.

A few weeks into the pandemic, the Medical Group Management Association found that COVID-19 had a negative financial effect on 97% of the 724 medical practices it surveyed.

Texas

And in an online survey conducted in early May, the Texas Medical Association found that 68% of practicing physicians in that state had cut their work hours because of COVID-19, while 62% had their salaries reduced. A concerned, long-time patient—with her physician’s blessing—set up a GoFundMe page on April 20 for a Dallas family medicine practice. In a month, it raised $96,766.

Indiana And New York

State medical associations in Indiana and New York have reported similar effects of the pandemic on medical practices.

Georgia

Meanwhile, in Georgia, “we dropped down to seeing 20% or 30% of our practice,” said Fayetteville pediatrician Sally Goza, MD, president of the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP). “Unfortunately, we had to furlough 3 of the employees just in our pediatric area, because we really didn’t have the work.” Goza’s practice includes internists and family practitioners as well as 4 pediatricians, 1 who works part time.

States and local jurisdictions have eased stay-at-home orders, and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has lifted some restrictions on nonemergent, non–COVID-19 care, so business has recently picked up in physician practices. But physicians report that it is still well below prepandemic levels and is expected to stay that way, at least as long as social distancing is required.

On May 19, the Commonwealth Fund published an analysis of data from more than 50 000 physicians in all 50 states who use products from Phreesia, a health technology company. An earlier study, published April 23, found a nearly 60% drop in visits to ambulatory care practices early in the pandemic. The more recent analysis found that practices had rebounded, but visits were still roughly a third lower than before the pandemic.

In a survey of 558 US primary care physicians fielded May 29 through June 1—nearly 3 months into the pandemic—6% of respondents said their practices were closed, perhaps temporarily, and 35% said they’ve furloughed staff, according to the nonprofit Primary Care Collaborative (PCC) and the Larry A. Green Center.

“Unfortunately, I think this [pandemic] is going to accelerate the closure of the smaller practices,” said Andrew Kleinman, MD, a plastic surgeon with a solo practice in Rye Brook, New York. “With a lot of practices, 40% or more of their revenue goes just to overhead.”

Staying Away

Although people packed beaches and boardwalks after restrictions lifted and Black Lives Matter demonstrators flooded city streets and parks, many patients, often older and in poor health, still seem reluctant to visit physician offices.

The PCC and Green Center physician survey found that 79% of respondents continued to report fewer patient visits compared with before the pandemic.

“As a country, we did a very good job of explaining there was this sudden, horrible virus going around,” said Ateev Mehrotra, MD, MPH, a health policy researcher at Harvard Medical School and a hospitalist at Beth Israel Deaconess Hospital.

But that message might have had an unintended consequence, said Mehrotra, a coauthor of the Commonwealth Fund analysis. “We got people scared of going to the doctor’s office or the hospital,” he said. “They would rather die at home than get exposed to the coronavirus.”

The cause of some of the excess US deaths that have occurred since mid-March might not be COVID-19 itself but the fear it generated, preventing people from seeking medical care for symptoms that require immediate attention such as chest pain, Mehrotra speculated.

“Patients are still fearful,” said Mildred Frantz, MD, the sole physician in her Eatontown, New Jersey, family medicine practice. Some days, she said, she’ll look at the next day’s schedule and think, “Oh, that’s not bad, it’s three-quarters full.”

When the next day rolls around, though, maybe half of the scheduled patients don’t show up, Frantz said. “That’s not good. We run on small profit margins.”

Desperate to keep her practice afloat, Frantz created a GoFundMe page on April 10. “I felt conflicted about whether I should do it,” she said weeks later. She struggled with the notion of holding out a hat to friends and patients and their families, finally deciding not to, although she hadn’t yet taken the page down as of mid-June.

Many people have lost their jobs and, as a result, their health insurance because of the pandemic, noted Glynis Thakur, a business consultant based in Bellevue, Washington, who works with physician practices. “It’s not going back to normal any time soon,” she said. Thakur was so concerned about the survival of the practices she works with that she created a GoFundMe page to raise money for them. But she abandoned that plan after raising $250 of a $50 000 goal because she’s not on social media to promote it.

Affordability, cited by 40% of respondents, was patients’ biggest obstacle to obtaining primary care, the PCC and Green Center found in a survey fielded May 22 through May 25.

In the same survey, a quarter of respondents said they stayed away from primary care practices “so as not to be a bother,” because they assumed their physician was swamped due to the pandemic.

Crested Butte, Colorado, pediatrician Jennifer Sanderford, MD, can attest to that. Sanderford is the only pediatrician in 3 counties, and, she said, patients and their parents figured she was busy taking care of sick children. They could not have been more wrong. As noted in an April AAP blog post, business in Sanderford’s practice plummeted by 95% in the early weeks of the pandemic. She feared she would have to shut down the practice she’d spent 20 years building.

Pediatric Patients Go AWOL

The AAP in May launched a social media campaign, “#CallYourPediatrician,” to remind parents that they should still make appointments for well-child checks and immunizations during the pandemic.

Research supports pediatricians’ concerns that children have been falling behind in their immunizations. Compared with the same time period in 2019 and 2018, vaccination coverage of Michigan infants and toddlers up to age 2 years declined in January through April of 2020, according to a recent article in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Only coverage with the hepatitis B vaccine dose given at birth, typically in the hospital, did not decrease.

“The observed declines in vaccination coverage might leave young children and communities vulnerable to vaccine-preventable diseases such as measles,” the authors noted.

When Sanderford finally received money from the federal Payroll Protection Program in early May, she sent an email blast to all her patients’ families. “We were very forthcoming,” she said, explaining her practice’s financial straits and the need for vaccinations and well-child checks. “We are slowly getting to the end of our list of patient well checks that were due,” she said at the beginning of June, although business is still well below prepandemic levels.

Pediatrics is among the specialties particularly hurting during the pandemic, according to the Commonwealth Fund’s recent analysis. One disadvantage they face is that very few of their patients are Medicare beneficiaries, Goza, representing the AAP, noted in a letter April 16 to Alex Azar, secretary of the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS).

“Pediatricians have not been able to access financial relief policies issued by HHS because of the focus on Medicare” payments, she pointed out in the letter. “[T]hey have not been eligible for Medicare advanced or accelerated payments, they have not been able to access increased Medicare payments for care related to COVID-19.”

Door Shingles Replaced With “Closed” Signs

From the middle of March until the last week of May, “I basically had no income,” said Kleinman, a solo practitioner who closed his office for several weeks and laid off 5 full-time and part-time staff members.

When pediatricians occasionally referred patients with lacerated lips that needed stitches, he said, he’d check with his wife, a nurse practitioner who works in occupational health, to see when she’d be available to assist him.

Kleinman, a past president of the Medical Society of the State of New York, said he reduced his malpractice coverage to half-time, but he still had to pay two-thirds of his prepandemic premium. “For a plastic surgeon, it’s still expensive when there’s no income.” And he still had to pay other overhead costs—phones and electronic medical records, to name 2—for his temporarily closed practice.

“If this happened to me 20 years ago, I would be bankrupt,” said Kleinman, who, at age 66 years, was able to draw on savings to help his practice survive. “When this whole thing started, I strongly considered just retiring now.” While he’s heard of physicians retiring early rather than waiting out the pandemic, Kleinman said, he decided he’s not yet ready to follow suit.

Joseph Valenti, MD, an obstetrician and gynecologist in Denton, Texas, says he couldn’t perform surgery for 6 weeks, resuming only in mid-May, because Medicare deemed his procedures nonemergent. “We just can’t wait forever,” he said, noting that some of his patients needed to have premalignant lesions removed.

“So many practices like ours were in trouble before the COVID thing,” said Valenti, who had stopped practicing obstetrics before the pandemic struck. “It’s now much worse.”

His office closed except for his associates’ obstetrics patients, and the practice, now comprising 5 physicians, 3 nurse midwives, and 1 nurse practitioner, had to lay off its other nurse midwife and temporarily reduce the nurse practitioner’s salary, he said.

“We did a lot of telehealth and were working from home,” Valenti said, and his practice still is open only 4 days a week—with shorter hours—instead of the usual 5.

The main issue, which predates the pandemic, has been that small practices have no money in reserves, he said, noting that his salary is lower than it was when he started practicing in Denton in 1998. “I have a stack of paperwork here for debts owed to pharmaceutical companies for birth control,” Valenti said. “Hopefully, they’re willing to work with us.”

Turning to Telehealth

In the early days of the pandemic, CMS expanded coverage of and access to telehealth services to minimize Medicare beneficiaries’ need to seek care at a physician’s office or a hospital.

“There’s been this tremendous, tremendous rise in the use of telemedicine,” Mehrotra said. “A change that I would have expected over a decade happened in a month.” About 14% to 15% of all patient visits are now telemedicine, he said.

Telemedicine has helped make up for some of the decline in office visits, but far from all of it. While his office was closed, Valenti said, “I was doing maybe 3, 4, or 5 telehealth visits a day.” But prepandemic, he’d typically see 13 to 15 gynecology patients each day.

As many as 40% of patient visits could be handled via telemedicine, Mehrotra said. However, many practices are reluctant to commit the necessary resources because it’s not clear whether they’ll continue to be reimbursed for telemedicine visits after the pandemic ends, he said.

On June 11, the American College of Physicians sent letters to the presidents and CEOs of the Blue Cross Blue Shield Association, UnitedHealth Group, the National Association of Insurance Commissioners, and America’s Health Insurance Plans, that, among other recommendations, urged them to continue paying for telehealth, no matter the platform, at the same rate as in-person services after the public health emergency ends.

“It’s not a thing that you can flip on a switch that easily,” said Mehrotra, who coauthored a recent article outlining the strategies for implementing regular use of telemedicine. Practices need to figure out the logistics—the when and where of telemedicine visits—and “we need to train the patients,” he said.

All the training in the world won’t help patients if they don’t feel comfortable using the technology or don’t have access to it, he said. While that probably isn’t much of an issue in obstetrics practices because a high percentage of pregnant women have cell phones, it could be a huge stumbling block for geriatricians, Mehrotra said.

The CMS recently expanded telemedicine coverage again to include services delivered by audio-only telephone calls, which likely would help patients who lack Wi-Fi and a computer. For some families receiving Medicaid, though, even telemedicine by telephone is out of reach, Sanderford said. They might have only 1 cell phone, and it goes to work with the father, she explained.

Practices Trying to Make Perfect

The COVID-19 pandemic has forced practices to take the wait out of waiting rooms, as physicians struggle to see as many patients as possible while maintaining social distancing in their offices.

“The same physical footprint cannot be used for the same number of patients,” Mehrotra noted.

Before the pandemic, Frantz said, her waiting room seated a dozen people. Now, it contains only 3 chairs, each placed against a different wall. Particularly high-risk patients skip the waiting room altogether and remain in their car until their appointment. When patients simply need to drop off a urine sample, they wait in their car until a member of Frantz’s staff comes out to retrieve it.

For now, Kleinman said, he is scheduling only 1 patient per hour, even though he has 3 examination rooms. “I really want to minimize the overlap.”

One of his staff calls patients the day before their appointment to ask whether they have any possible COVID-19 symptoms. If so, they are rescheduled for a later date. When patients arrive for an appointment, they call from their car to make sure the coast is clear for them to come up to the office.

Kleinman, who performs surgical procedures in his office, not in a hospital, feels lucky that he was able to obtain two 20-count boxes of N95 respirators, albeit “at an outrageous price.” And he was able to buy an extra gallon of the sanitizer—“a higher level than a Clorox wipe”—he uses to disinfect surfaces.

Soon, Kleinman said in late May, he planned to begin scheduling 2 patients per hour, seating 1 in his waiting area and 1 in an examination room. “I expect my income to be down by 50% for the next month or 2,” he said. “I don’t think it will get back to normal before there is a vaccine.”

Talking to my once-upon-a-time primary care physician I asked him, “So. If I get injured, when I wake up in a hospital you’ll be attending to me, right?” He said, “Oh no. I couldn’t do that. I’d go broke! I have to see 35 patients a day just to break even! After being with me for a short while there was a loud knocking on the exam room door. “Who’s knocking” I asked the doc. “That’s one of my nurses letting me know I’m spending too much time with you.”

The days of doctors saying hello, taking a quick look, writing a prescription for expensive pills from Big Pharma and leaving the room are gone.

700,000 not-yet-desperate US doctors (before Covid) killed 780,000 people a year. Those numbers have to be even more scary now since doctors can get $40 grand just for putting a patient on a respirator (which nearly always kills the patient) and then claiming the patient died of Covid.

Plandemic Wrongdoing

- • In the Second Greatest Depression Of 2008 . . . the feds secretly paid banks $50 grand for each foreclosure that threw an American family out on the street. Doctors now get $40 grand for killing a patient with a respirator and claiming “it was Covid.”

- • The FDA and CDC (who are supposed to guard the public from unsafe drugs) enthusiastically recommend the untested and unsafe Covid vaccines and boosters because their salaries now come from Big Pharma who make the vaccines and profit from selling them to the government.

- • After the vaccine roll-out Covid deaths went up not down. More patients died in the vaccine group than patients in the placebo group.

- • Big Pharma has been caught lying about vaccine test data.

- • Suspicious nurses are sending in unused Covid nasal swabs to be tested. These swabs test positive for Covid. Scaring patients about the SIZE of the plandemic makes them more likely to agree to be vaccinated.

- • Doctors continue to be allowed to write negative and disparaging comments in their patients secret federal medical database. Patients are not allowed to view or contest the doctor’s remarks! Dreadful comments by doctors can prevent a patient from (1) getting a new job and (2) getting new health insurance coverage since all employers and all health insurance companies can view these secret records.

- • Patients must be careful about letting doctors or hospitals “take blood” because the patient’s DNA can be recorded in the secret federal medical database along with any predisposition the patient might have for life-threatening diseases the DNA reveals. Insurance companies can then use the stolen DNA, taken without the patient’s knowledge or permission, to avoid providing medical coverage by claiming “pre-existing conditions.”

Medicine in the US was crooked and dangerous before. Now it’s crooked and lethal.

My plan? I plan to stay well away from doctors from now on. I was waiting for a lady friend to recover from the Demerol drugging that was part of a horrible, miserable, throw up distasteful, “never again” colonoscopy. As I waited for her to “come to,” a doctor, walking past, asked me, “Do you really have to sit there? Couldn’t you wait in your car and have a nurse call you when your friend is ready to leave the hospital? A hospital IS NOT A GOOD PLACE TO HANG OUT. Every disease known to man is in this building! Give the nurse your phone number and wait outside . . . PLEASE!”

Later, I learned about the absolute foolishness of hospitals who remove the seat covers from all toilets. Every time a sick person flushes, therefore, an invisible plume of contagious micro-droplets floats out of the patient’s room and 100 feet or so down the hallways in both directions. It’s just like cutting up onions. The invisible micro-droplets float up to your eyes and make you cry. What floats out of hospital toilets?

- • Coronavirus

- • Norovirus

- • Clostridium Difficile (C Diff)

- • Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS)

And WHY do hospitals remove the toilet seats? “Because patients don’t use them.” Not good enough! Not good enough at all !Put up signs.

ALWAYS

PUT THE TOILET SEAT DOWN

BEFORE FLUSHING

IF WE CATCH YOU SKIPPING THIS STEP

THE FINE IS $2,000

Then there’s the stupidity of making room visitors wear cheap masks, tissue paper jackets, pants and gloves BUT NO EYE PROTECTION! Does anyone know or care that THE EYES lead straight to sinuses? It is thought that 3 micro droplets carrying a disease contagion landing on the eyes is enough to convey the disease, floating in the air from the (uncovered!) just-flushed toilet, to the soon-to-be-sick person.

Do hospitals know how to generate lots of new sick people (customers) or what?

So . . . in summary . . . this MESS is what we call “health care” in the USA.

###